The Intricacies of Welding Titanium to Steel: An Overview

Welding titanium to steel presents one of metallurgy's toughest challenges. These two powerhouse materials, renowned for their individual strengths, often resist direct fusion. Their distinct properties clash, threatening joint integrity. Engineers face a real tightrope walk.

However, the demand for joining these dissimilar metals is growing. Industries like aerospace, chemical processing, and marine engineering often require the corrosion resistance and strength-to-weight ratio of titanium coupled with the structural integrity and cost-effectiveness of steel. Achieving a reliable, robust connection between them is paramount.

This guide unpacks the complexities of welding titanium to steel, offering practical solutions and insights for engineers and fabricators aiming for success. We’ll delve into the science, the techniques, and the critical considerations that turn a potential headache into a high-performance reality.

Material Science Fundamentals: Titanium and Steel Properties

Understanding the core properties of both titanium and steel is the first step toward successful dissimilar metal joining. Their individual characteristics dictate the entire welding strategy.

Titanium Alloys: A Closer Look

Titanium boasts an exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, superb corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility. Its melting point sits around 1668°C (3034°F). It readily reacts with oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen at elevated temperatures, forming brittle compounds. This reactivity demands stringent shielding during welding. Common alloys like Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5) are frequently used, known for their high strength and fatigue resistance.

For detailed specifications on various titanium grades and their applications, refer to the extensive resources available on China Titanium Factory's product pages.

Steel Types and Their Characteristics

Steel, an alloy of iron and carbon, offers a wide spectrum of properties depending on its composition. Carbon steels are strong and economical. Stainless steels (e.g., 304, 316L) provide corrosion resistance through chromium content. Alloy steels incorporate elements like nickel, molybdenum, and manganese to enhance strength, toughness, and hardenability. Steel's melting point is typically lower than titanium's, ranging from 1370-1530°C (2500-2785°F).

The choice of steel significantly impacts welding parameters and potential issues.

Navigating the Complexities of Dissimilar Metal Welding

Directly fusing titanium and steel is akin to mixing oil and water; they don't play well together. The core issues stem from fundamental metallurgical incompatibilities. Ignoring these leads to catastrophic weld failures.

Intermetallic Compound Formation

The most significant hurdle is the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds, specifically iron-titanium (Fe-Ti) phases. These compounds, such as FeTi and Fe₂Ti, are extremely hard and fragile. They form readily in the fusion zone when molten titanium and steel mix. A small percentage of these phases can severely degrade weld ductility and toughness, making the joint prone to cracking under stress.

Intermetallic Compound: A chemical compound formed between two or more metallic elements, possessing a distinct crystal structure and often exhibiting properties significantly different from its constituent metals, frequently brittle.

Thermal Expansion Mismatch

Titanium and steel possess different coefficients of thermal expansion. Steel generally expands more than titanium when heated. During welding, the rapid heating and cooling cycles create significant differential stresses at the joint interface. As the weld cools, these stresses can lead to cracking, distortion, and residual stress build-up. Managing this mismatch is crucial for joint stability.

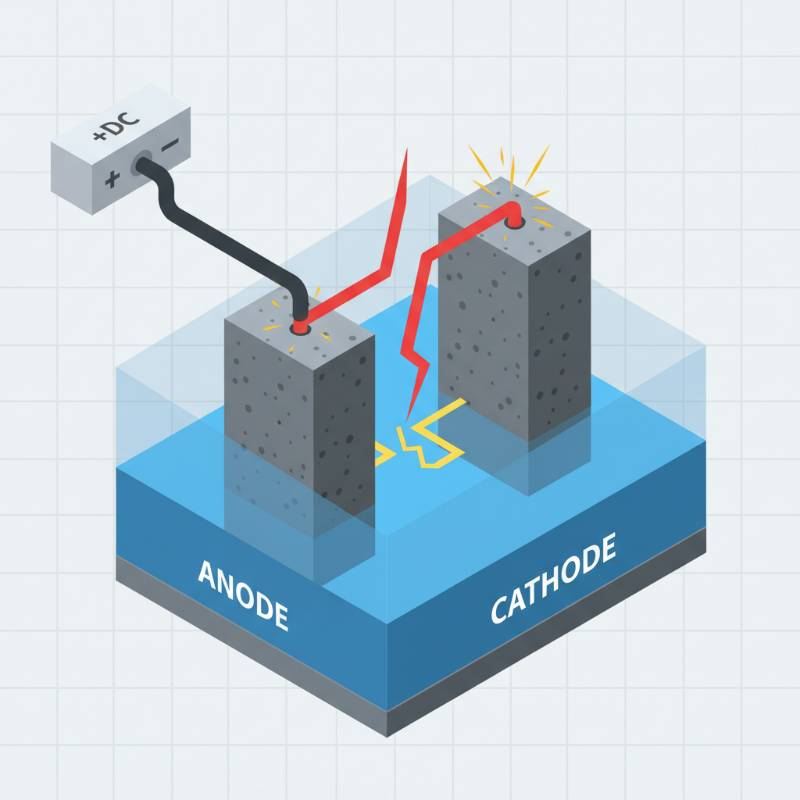

Galvanic Corrosion Risk

When two dissimilar metals are joined in the presence of an electrolyte (like seawater or even atmospheric moisture), a galvanic cell can form. Titanium is noble, while most steels are less noble. This electrochemical potential difference can accelerate corrosion of the less noble steel, especially at the weld interface. This is a critical consideration for marine or chemical processing applications.

For more on material compatibility and corrosion resistance in demanding environments, consult an authority like NACE International (now part of AMPP) for industry standards on corrosion prevention (source).

Critical Pre-Welding Procedures for Titanium and Steel

Meticulous preparation is non-negotiable. Skipping steps here guarantees failure. Getting it right ensures the best shot at a sound weld.

Surface Cleaning and Preparation

Both titanium and steel surfaces must be pristine. Oxides, grease, oil, paint, and contaminants are enemies of a good weld. For titanium, mechanical cleaning (wire brushing with stainless steel brushes only used for titanium) followed by chemical cleaning (acetone or methyl ethyl ketone) is standard. For steel, grinding or machining to remove scale and rust is essential, followed by solvent cleaning. Never cross-contaminate tools between materials.

Joint Design Considerations

Careful joint design minimizes dilution and manages stress. Beveling is common. For thin sections, a simple butt joint might work with an intermediate layer. Thicker sections often require a V-groove or U-groove. The goal is to control the weld pool and reduce the mixing of the two base metals as much as possible. A narrow gap helps. Expertise in custom fabrication and precise machining is vital here.

Fixturing and Thermal Management

Proper fixturing is critical to prevent distortion from thermal expansion differences. Copper backing bars can act as heat sinks to control the cooling rate. Preheating is generally avoided for titanium due to its reactivity, but localized preheating of the steel side might be considered in specific cases to reduce thermal gradients, though this is a delicate balance. Always consult material specialists for such decisions.

Effective Strategies for Welding Titanium to Steel: Techniques and Methods

Direct fusion welding of titanium to steel is largely impractical due to the brittle intermetallic phases. Smart strategies involve avoiding direct contact or employing solid-state methods. Think outside the box.

Fusion Welding with Intermediate Buffer Layers

This is a widely adopted approach. A third material, compatible with both titanium and steel, is introduced as an intermediary. This buffer layer prevents direct mixing of iron and titanium. Common choices for buffer layers include:

Vanadium: Acts as a good diffusion barrier.

Nickel or Nickel Alloys (e.g., Inconel): Excellent for joining to steel, then titanium can be welded to the nickel layer. Nickel forms stable compounds with both iron and titanium, reducing the formation of brittle Fe-Ti phases.

Copper: Can be used, particularly in explosion welding, to create a graded transition.

The process often involves cladding the steel with the buffer material first, then welding the titanium to this clad layer. This significantly reduces the risk of intermetallic formation. Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW) with pure argon shielding is often preferred for its precise heat control and inert atmosphere, crucial for titanium.

Solid-State Welding Processes

These methods avoid melting the base metals entirely, thereby eliminating the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds. They are excellent for welding titanium to steel.

Friction Stir Welding (FSW): A non-consumable rotating tool generates frictional heat, plasticizing the materials. The tool then stirs and forges the materials together. FSW creates fine-grained microstructures and is highly effective for dissimilar metal joining, including titanium to steel, by minimizing intermetallic formation.

Diffusion Bonding: Surfaces are brought into intimate contact under high pressure and temperature (below melting point). Atomic diffusion occurs across the interface, forming a metallurgical bond. This process typically requires vacuum or inert gas atmospheres and carefully prepared surfaces.

Explosion Welding: This involves detonating an explosive to force two metals together at high velocity. The impact creates a solid-state metallurgical bond with minimal heat input, effectively overcoming solubility issues. This method is often used for cladding large plates.

Specialized Brazing Methods

Brazing uses a filler metal that melts at a lower temperature than the base metals. For titanium-steel joints, active brazing alloys containing titanium or zirconium can wet the titanium surface, while other elements facilitate bonding to steel. Vacuum brazing or inert atmosphere brazing is essential to prevent oxidation. This technique can produce high-quality joints, especially for complex geometries or thin sections.

Laser and Electron Beam Welding

These high-energy density processes offer precise heat input control and minimal heat-affected zones. While still challenging for direct titanium-steel fusion, they can be highly effective when combined with intermediate layers or for very fast, localized welding that limits intermetallic growth. Electron beam welding, performed in a vacuum, provides an ideal inert environment for reactive metals like titanium.

For complex applications demanding precision, such as those requiring specialized titanium welding services, partner with a factory possessing advanced capabilities and experienced personnel. China Titanium Factory offers comprehensive solutions for these demanding processes.

Post-Welding Treatment and Inspection for Dissimilar Joints

The job doesn't end when the arc stops. Post-weld treatments and rigorous inspection are vital to ensure the joint holds up under real-world conditions.

Post-Weld Heat Treatment (PWHT)

PWHT can be a double-edged sword for dissimilar joints. While it can reduce residual stresses and improve ductility in steel, it might also promote further intermetallic formation or cause adverse microstructural changes in titanium. Therefore, PWHT for titanium-steel joints must be carefully considered and optimized based on the specific materials and welding process used. Often, it's avoided or performed at very specific, low temperatures for short durations.

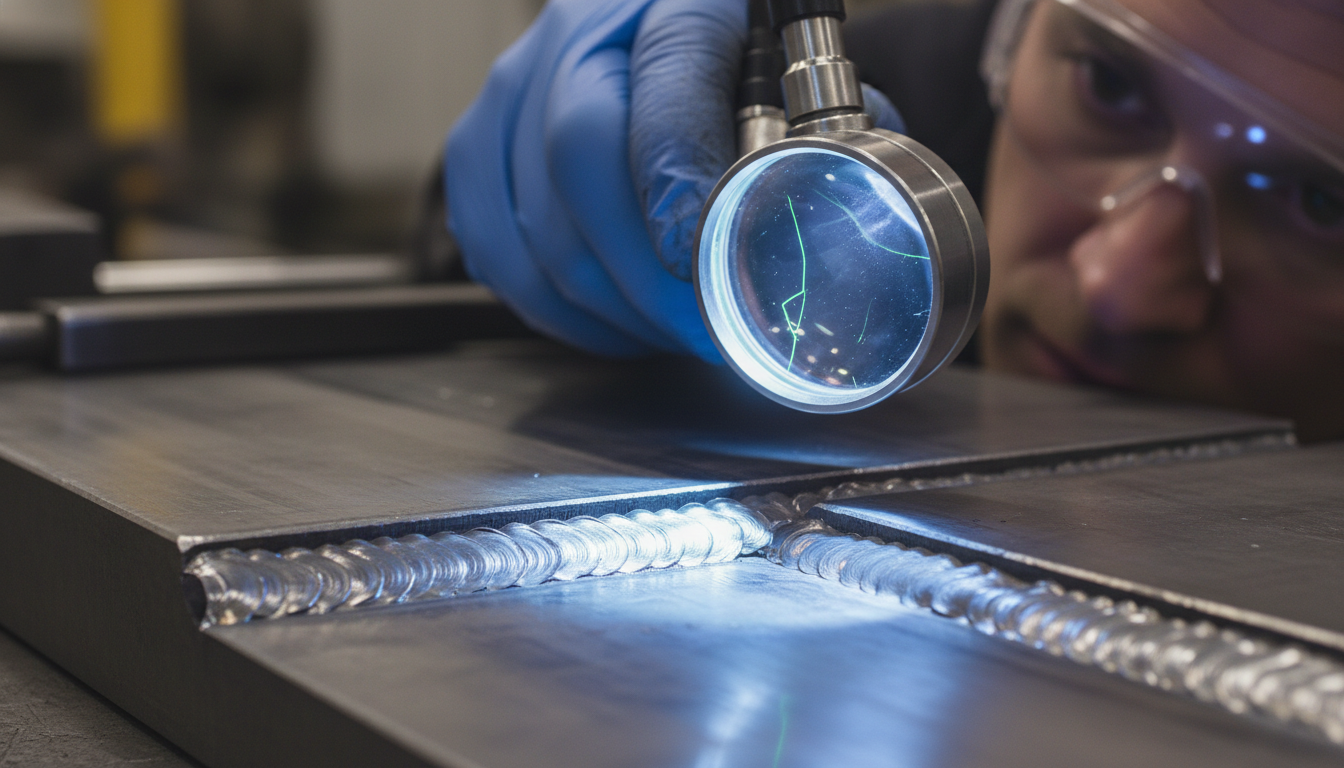

Non-Destructive Testing (NDT)

NDT methods are crucial for verifying weld integrity without damaging the component. These include:

Visual Inspection: First line of defense for surface defects like cracks, porosity, or discoloration.

Radiographic Testing (RT): X-rays or gamma rays detect internal flaws like porosity, inclusions, or lack of fusion.

Ultrasonic Testing (UT): High-frequency sound waves detect internal flaws and can characterize bond interfaces.

Liquid Penetrant Testing (PT) / Dye Penetrant Inspection (DPI): Reveals surface-breaking defects.

Eddy Current Testing (ET): Detects surface and near-surface flaws and can also measure coating thickness.

Destructive Testing Methods

For process qualification and sample verification, destructive tests provide in-depth mechanical and metallurgical data.

Tensile Testing: Measures strength and ductility.

Bend Testing: Assesses ductility and soundness.

Impact Testing: Determines toughness, especially for critical applications.

Hardness Testing: Identifies variations in material properties across the weld zone.

Metallographic Examination: Microscopic analysis of the weld microstructure, crucial for detecting intermetallic phases and evaluating bond quality.

Stringent quality control protocols, including both NDT and destructive testing, are integral to ensuring the reliability of dissimilar metal welds. Reputable manufacturers adhere to international standards like those from the American Welding Society (AWS) or ISO (source).

Safety Considerations for Welding Titanium and Steel

Welding, by its nature, carries risks. Dissimilar metal welding, especially with reactive materials like titanium, adds another layer of complexity. Safety is paramount; no cutting corners.

Ventilation Requirements

Adequate ventilation is non-negotiable. Welding fumes from steel can contain hazardous particulates, while titanium welding can produce fine titanium oxide particles. Local exhaust ventilation (LEV) systems are highly recommended to capture fumes at the source. General room ventilation also plays a role in maintaining air quality.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Standard welding PPE applies: welding helmet with appropriate shade, flame-retardant clothing, gloves, safety glasses, and steel-toed boots. For titanium welding, additional respiratory protection (e.g., powered air-purifying respirators, PAPRs) may be necessary, especially in enclosed spaces, to protect against fine particulates.

Fire Prevention and Hazard Management

Titanium dust and fine chips are highly flammable and can ignite explosively. Welding titanium should always be done in a clean area, free from combustible materials. Grinding titanium creates sparks; ensure proper collection and disposal of titanium grinding dust. Have appropriate fire extinguishers (Class D for metal fires) readily available. Avoid water on titanium fires, as it can react violently.

Troubleshooting Common Defects in Titanium-Steel Welds

Even with the best preparation, defects can creep in. Knowing how to spot and fix them is part of the game.

Intermetallic Cracking

Cause: Excessive dilution, insufficient buffer layer, or incorrect welding parameters leading to too much Fe-Ti compound formation.

Solution: Optimize buffer layer thickness and composition. Reduce heat input. Adjust travel speed. Consider alternative joining methods like FSW.

Porosity

Cause: Inadequate shielding gas coverage (for reactive titanium), contaminated base metal surfaces, or moisture in the shielding gas.

Solution: Ensure robust inert gas shielding (argon, trailing shields). Thoroughly clean surfaces. Check gas lines for leaks and moisture.

Lack of Fusion or Penetration

Cause: Insufficient heat input, improper joint design, or incorrect electrode manipulation.

Solution: Increase welding current or decrease travel speed. Re-evaluate joint geometry. Improve welder technique.

Distortion and Residual Stress

Cause: High heat input, large thermal gradients, or inadequate fixturing, exacerbated by thermal expansion mismatch.

Solution: Use lower heat input processes. Employ proper clamping and fixturing. Consider controlled preheating/postheating of the steel side, if appropriate and carefully managed.

A deep understanding of metallurgy and hands-on experience are invaluable here. Don't be afraid to lean on experts, especially when dealing with such critical joints.

Industrial Applications and Case Studies of Titanium-Steel Joints

The challenges are real, but so are the rewards. Successful titanium-steel joints are enabling advancements across various high-stakes industries.

Aerospace and Defense

Weight reduction is king in aerospace. Titanium's high strength-to-weight ratio makes it ideal for aircraft components, but cost and ease of fabrication often necessitate joining it to steel structures. Examples include landing gear components, engine parts, and structural connections where specific zones require titanium's properties. Explosion welding and FSW are often employed for these critical applications.

Marine and Offshore Engineering

Corrosion in seawater is a relentless foe. Titanium's exceptional corrosion resistance makes it perfect for heat exchangers, piping, and submersible components. Joining these titanium sections to steel hulls or structural elements requires careful consideration of galvanic corrosion. Buffer layers or specific solid-state welding techniques are critical to ensure longevity in these harsh environments. For instance, clad plates are used in shipbuilding to transition between titanium and steel sections.

Chemical and Petrochemical Processing

Aggressive chemical media demand materials that won't corrode. Titanium is a go-to for reactors, vessels, and pipelines handling highly corrosive fluids. Integrating titanium components into larger steel plant infrastructure often relies on expertly welded dissimilar joints. Here, the focus is on maintaining corrosion resistance at the interface. Reputable fabricators, like China Titanium Factory, understand these critical demands.

Medical and Biomedical Devices

Biocompatibility is paramount. Titanium is widely used for implants and surgical instruments. While direct implants are titanium, connections to other metallic components or manufacturing fixtures might involve steel interfaces. Precision laser welding or diffusion bonding techniques, often on a micro-scale, are employed to achieve defect-free, sterile joints.

Cost Implications and Budgeting for Titanium-Steel Welding Projects

Welding titanium to steel isn't a budget operation. The specialized nature of the materials and processes translates into higher costs than conventional steel welding. Understanding these factors is key to effective project budgeting.

Material Costs

Titanium itself is significantly more expensive than steel. When intermediate buffer layers (e.g., nickel alloys, vanadium) are required, these also add to the material budget. Factor in the cost of specialized filler metals and high-purity shielding gases.

Equipment and Labor

Advanced welding techniques often require specialized equipment (e.g., FSW machines, vacuum chambers for diffusion bonding/brazing, laser welding systems). The labor costs are also higher due to the need for highly skilled, certified welders and technicians with specific expertise in dissimilar metal joining. This isn't a job for just any welder; it calls for the cream of the crop.

Testing and Qualification

The rigorous NDT and destructive testing discussed earlier contribute significantly to project costs. Qualification of welding procedures and personnel also involves substantial investment. These steps are non-negotiable for critical applications, ensuring the integrity and reliability of the joint.

Long-Term Value Proposition

Despite the higher initial outlay, the longevity, performance, and corrosion resistance of properly executed titanium-steel joints often provide a superior long-term value. Reduced maintenance, extended service life, and enhanced operational efficiency can quickly offset the upfront investment. It's an investment in reliability and performance. For precise cost estimates and project planning, contact China Titanium Factory for a consultation.

Frequently Asked Questions About Welding Titanium to Steel

Q: Is it possible to directly weld titanium to steel?

A: Direct fusion welding of titanium to steel is generally not recommended and largely impractical for critical applications. The primary issue is the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds (Fe-Ti phases) in the weld zone, which severely compromise mechanical properties and lead to cracking. Specialized techniques involving intermediate buffer layers or solid-state welding processes are necessary for reliable joints.

Q: What are the biggest challenges when joining these two metals?

A: The main challenges include the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds, significant differences in thermal expansion coefficients leading to high residual stresses, and the risk of galvanic corrosion in service environments. Additionally, titanium's high reactivity with atmospheric gases at welding temperatures demands stringent shielding.

Q: What welding methods are most effective for titanium to steel?

A: The most effective methods either prevent direct mixing of the molten metals or avoid melting altogether. These include fusion welding with an intermediate buffer layer (e.g., nickel, vanadium), solid-state welding processes like Friction Stir Welding (FSW), Diffusion Bonding, and Explosion Welding, and specialized brazing techniques. Laser and Electron Beam welding can also be used, often with buffer layers.

Q: Why is an intermediate layer often used?

A: An intermediate buffer layer acts as a metallurgical barrier. It prevents the direct interaction between molten iron and titanium, thereby minimizing or eliminating the formation of brittle iron-titanium intermetallic compounds. The buffer material is chosen for its compatibility with both titanium and steel, allowing for two separate, more manageable welds.

Q: What industries benefit from welding titanium to steel?

A: Industries requiring both the unique properties of titanium (e.g., corrosion resistance, high strength-to-weight) and the structural or cost benefits of steel are the primary beneficiaries. This includes aerospace (lightweight structures), marine and offshore (corrosion resistance in seawater), chemical processing (handling aggressive media), and certain medical applications.