Titanium is considered a poor electrical conductor compared to common metals like copper or aluminum, exhibiting significantly higher electrical resistivity.

Its thermal conductivity is also low, classifying it as a relatively good thermal insulator among metals, making it suitable for applications requiring heat retention or resistance.

The unique combination of high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and specific conductive properties dictates titanium's specialized applications in aerospace, medical, and chemical processing industries.

Factors such as purity, alloying elements, and temperature significantly influence both the electrical and thermal conductivity of titanium and its alloys.

For specific titanium material requirements and expert guidance, resources like China Titanium Factory provide comprehensive solutions.

Titanium, a transition metal renowned for its exceptional strength-to-weight ratio and corrosion resistance, presents a unique profile concerning its electrical and thermal conductivity. While its mechanical properties are widely celebrated, understanding whether is titanium a conductive metal in electrical and thermal contexts is crucial for its appropriate application in diverse engineering fields. This guide explores the fundamental conductive properties of titanium, distinguishing it from other common engineering metals. It aims to clarify its role in applications where electrical flow or heat transfer are primary considerations. The discussion will cover both its intrinsic characteristics and the factors influencing its performance.

Titanium (Ti) is a chemical element with atomic number 22, situated in Group 4 of the periodic table. It is classified as a transition metal, known for its lustrous silver color. Its atomic structure, characterized by four valence electrons, dictates many of its physical and chemical properties. The element exists in two primary allotropic forms: alpha (hexagonal close-packed) at lower temperatures and beta (body-centered cubic) at higher temperatures. This structural versatility, often manipulated through alloying, contributes to its diverse material properties.

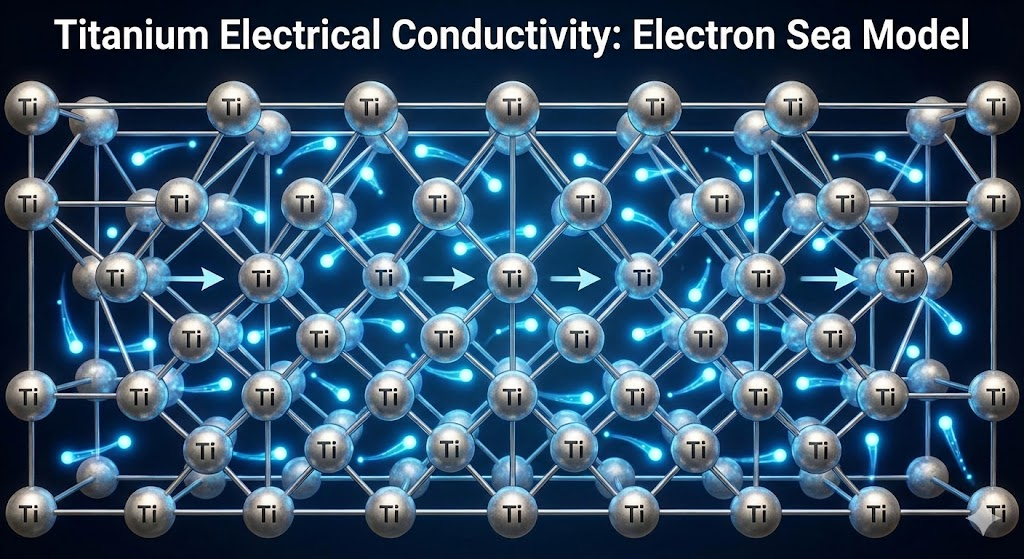

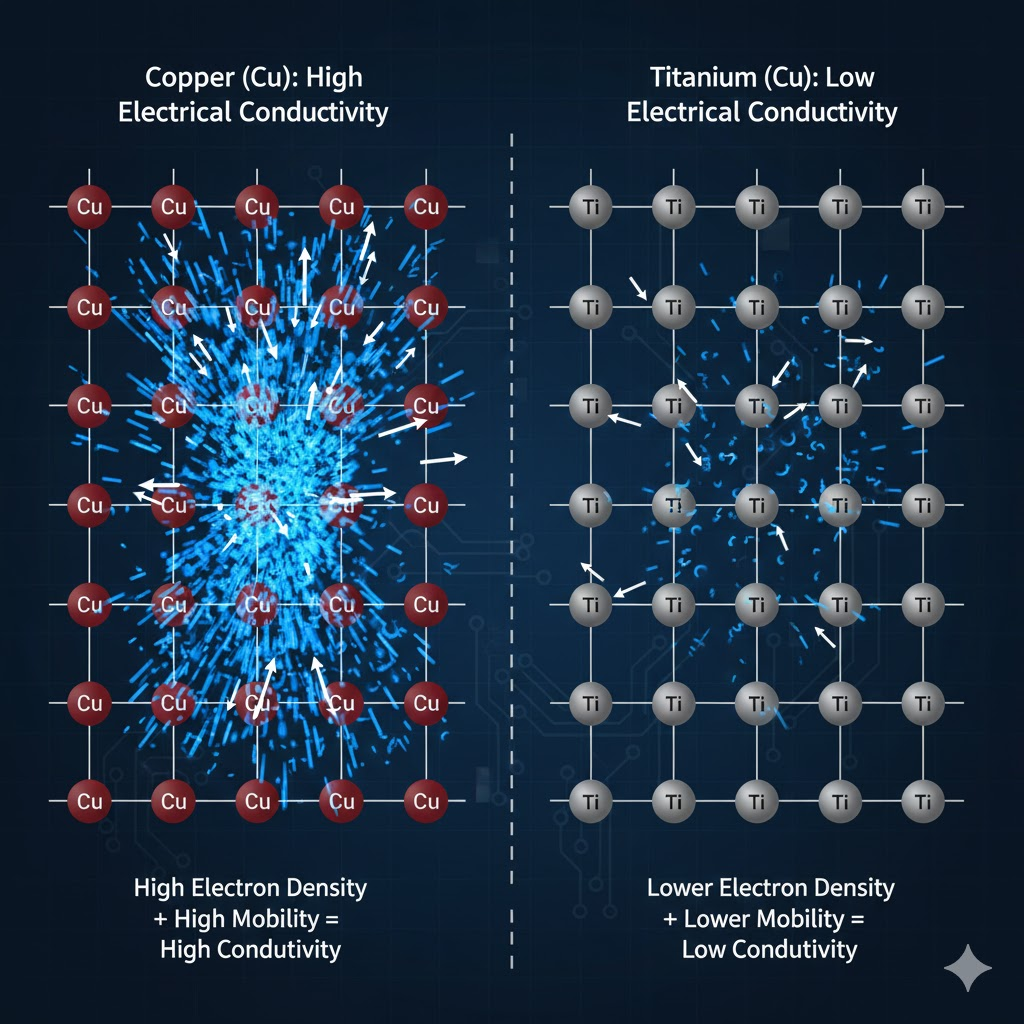

The electron configuration of titanium, specifically its d-block electrons, plays a critical role in its metallic bonding and subsequent interaction with electrical and thermal energy. While these electrons facilitate conductivity, their specific arrangement results in higher resistivity compared to metals with more freely delocalized s-orbital electrons like copper.

In the realm of electrical conductivity, titanium is generally considered a poor conductor when compared to more common metals used for electrical applications. Its electrical resistivity is significantly higher than that of copper or aluminum. For instance, the electrical resistivity of pure titanium at room temperature is approximately 0.55 µΩ·m. This contrasts sharply with copper, which has a resistivity of about 0.0168 µΩ·m, and aluminum, with approximately 0.0282 µΩ·m. This higher resistivity means titanium offers greater opposition to the flow of electric current. Consequently, it is not typically chosen for applications where efficient electrical transmission is paramount. The relatively limited electron mobility within titanium's crystal lattice contributes to its reduced conductivity. While it is certainly not an insulator, its performance places it far from the ideal electrical conductor category. For detailed data on material resistivity, one can consult resources like the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

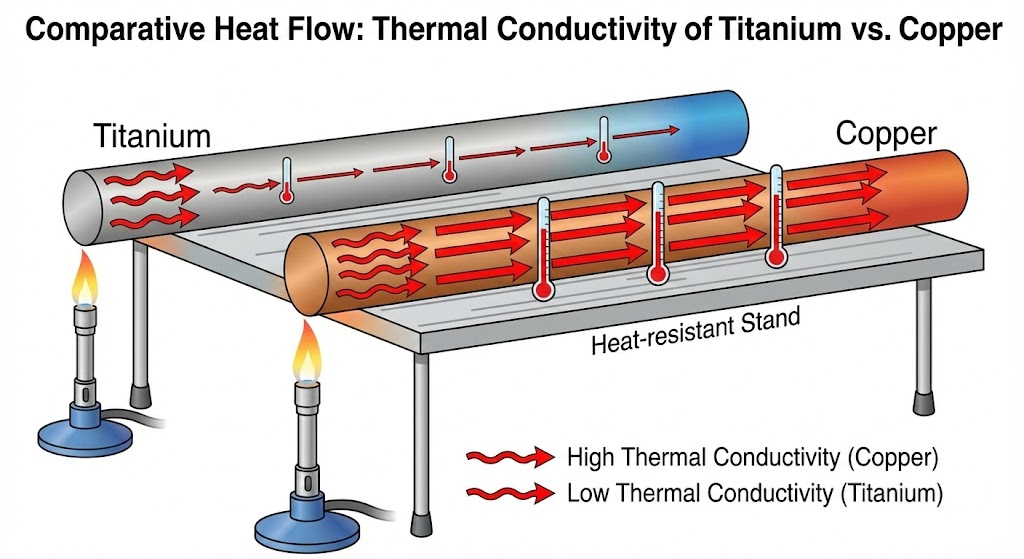

Regarding thermal conductivity, titanium again exhibits relatively low capabilities compared to many other metals. Its thermal conductivity at room temperature is approximately 21.9 W/(m·K). This value positions titanium as a moderate thermal insulator rather than an efficient heat transfer material. For comparison, copper possesses a thermal conductivity of around 401 W/(m·K), and aluminum is approximately 205 W/(m·K). The lower thermal conductivity of titanium means it does not readily transfer heat. This property can be both an advantage and a limitation, depending on the specific application. In scenarios requiring heat retention or resistance to rapid temperature changes, titanium's low thermal conductivity becomes beneficial. Conversely, for applications demanding efficient heat dissipation, titanium's properties necessitate careful design considerations.

To fully appreciate titanium's position, a direct comparison with other widely used engineering metals is essential. The following table illustrates the significant differences in electrical and thermal conductivity.

| Metal | Electrical Resistivity (µΩ·m at 20°C) | Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·K) at 20°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium (Pure) | 0.55 | 21.9 |

| Copper | 0.0168 | 401 |

| Aluminum | 0.0282 | 205 |

| Stainless Steel (304) | 0.72 | 15-17 |

| Silver | 0.0159 | 429 |

The table clearly demonstrates that titanium's electrical resistivity is significantly higher than that of highly conductive metals like copper, aluminum, and silver. Its thermal conductivity is also considerably lower. This positions titanium closer to materials like stainless steel in terms of thermal insulating properties, despite its superior strength-to-weight ratio.

Several factors can influence the electrical and thermal conductivity of titanium, altering its performance characteristics. Understanding these variables is critical for material selection and design.

The purity of titanium directly impacts its conductivity. Impurities, even in small concentrations, can scatter electrons and phonons, thereby increasing electrical resistivity and decreasing thermal conductivity. Higher purity titanium generally exhibits better (though still relatively low) conductivity.

The addition of alloying elements, such as aluminum, vanadium, or molybdenum, significantly alters titanium's conductive properties. These elements introduce lattice distortions and change electron density, typically reducing both electrical and thermal conductivity further compared to pure titanium. Titanium alloys, like Ti-6Al-4V, are formulated for specific mechanical properties, and their conductivity profiles are a consequence of their composition.

Both electrical and thermal conductivity of metals are temperature-dependent. As temperature increases, the atomic vibrations (phonons) within the crystal lattice become more energetic, leading to increased scattering of electrons and phonons. This typically results in higher electrical resistivity and, for most metals, a decrease in thermal conductivity at higher temperatures.

The specific crystal structure (alpha, beta, or alpha-beta phases) and the processing history (e.g., cold working, annealing) can also influence conductivity. These factors affect grain size, dislocation density, and texture, all of which impact the free path of electrons and phonons. For specialized titanium materials, exploring options at China Titanium Factory's services can provide insights into how processing affects properties.

While titanium's intrinsic conductivity is low, its alloys are sometimes engineered to balance specific properties. For example, some beta titanium alloys are developed with an emphasis on superplasticity or enhanced strength, accepting their inherently lower conductivity as a trade-off for other critical performance characteristics. The specific grade of titanium can drastically alter its mechanical and physical properties.

Titanium's unique conductive profile, characterized by relatively low electrical and thermal conductivity, plays a significant role in its suitability for various industrial applications. These properties are often considered alongside its high strength, low density, and exceptional corrosion resistance.

In aerospace, titanium's low thermal conductivity is advantageous in components exposed to high temperatures, such as engine parts and exhaust systems. It helps to localize heat, preventing its rapid spread to adjacent, heat-sensitive structures. This property, combined with its high melting point, makes it invaluable.

For medical implants like prosthetics and surgical instruments, titanium's low thermal conductivity means it does not conduct heat away from or towards the body as rapidly as other metals. This contributes to better thermal stability within the body, enhancing patient comfort and integration. Its biocompatibility and corrosion resistance are also critical factors here.

Titanium is widely used in heat exchangers and piping systems within aggressive chemical environments. While its thermal conductivity is low, its unparalleled corrosion resistance in these conditions often outweighs this limitation. Engineers design around the conductivity by increasing surface area or optimizing flow. More information on corrosion-resistant materials can be found on industry blogs and resources, such as those provided by China Titanium Factory's blog.

Despite its poor electrical conductivity, titanium finds niche applications where its other properties are paramount. For instance, in certain specialized electrical connectors or electrodes operating in corrosive environments, titanium's inertness and mechanical strength are prioritized over high conductivity. It is also used as a resistive material in some heating elements where its high melting point and stability are valued. For custom material solutions, contacting China Titanium Factory can provide expert assistance.

Visual aids are instrumental in comprehending complex material properties like conductivity. Infographics that depict electron flow through different metallic lattices can effectively illustrate why some metals are superior electrical conductors. Such visuals can show the relative density and mobility of free electrons in copper versus titanium. Similarly, diagrams illustrating heat transfer paths and temperature gradients across various materials provide clear insights into thermal conductivity. Interactive tools, such as online material property calculators, allow users to compare titanium's conductivity against other metals dynamically. These resources enhance understanding and facilitate informed material selection.

Whether your project demands specific conductive properties or the renowned strength and corrosion resistance of titanium, obtaining the right material is crucial. Partner with an expert supplier for quality and reliability.

Request a Quote TodayTitanium's conductive properties define its specialized role in materials science and engineering. It is not considered an efficient electrical conductor, exhibiting significantly higher electrical resistivity than metals like copper or aluminum. Similarly, its thermal conductivity is relatively low, positioning it as a moderate thermal insulator. These characteristics, however, are often advantageous when combined with titanium's superior strength-to-weight ratio, biocompatibility, and exceptional corrosion resistance. Factors such as purity, alloying, and temperature profoundly influence these properties. Understanding whether is titanium a conductive metal in specific contexts allows engineers to leverage its unique profile effectively across aerospace, medical, and chemical processing industries.